It is widely accepted that both formal and informal institutions matter in development processes and outcomes. For institutions to be effective they must complement local contexts and be designed by a mélange of local actors. When we examine how institutions are maintained, implemented and evolve, the answers point us to politics (Leftwich, 2011). Institutions are constructed to reflect the interests and ideas of actors involved in determining “the use, production and distribution of resources” (Leftwich, 2008, p. 6).

This week, I was urged to think more politically to work differently in development. It is fundamental that international actors understand the local political processes involved in building effective institutions to better align their projects and programs.

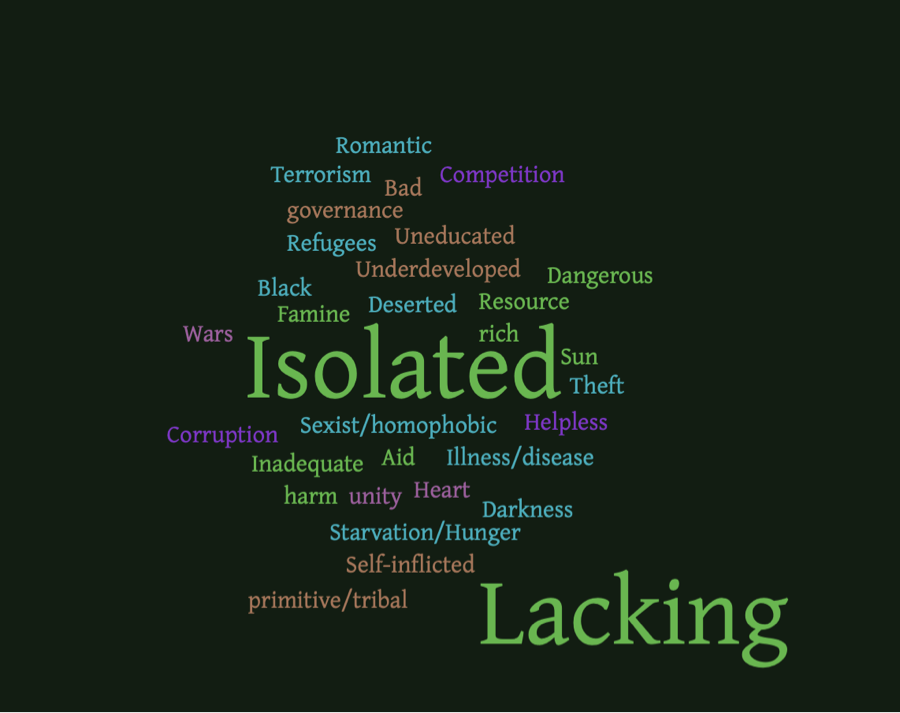

Currently, donors are paying attention to politics. Unfortunately, assumptions about how development happens remain static. Projects and programs continue to be technocratic, aimed at changing behaviors and practices deemed unfit for development. Unsworth (2009) suggests that thinking politically also requires delineating from this ethos and recognizing “unorthodox opportunities for progress” (p.884). Rather than fixing what has been inherently labeled wrong or problematic, there should be an emphasis on greater engagement with local structures.

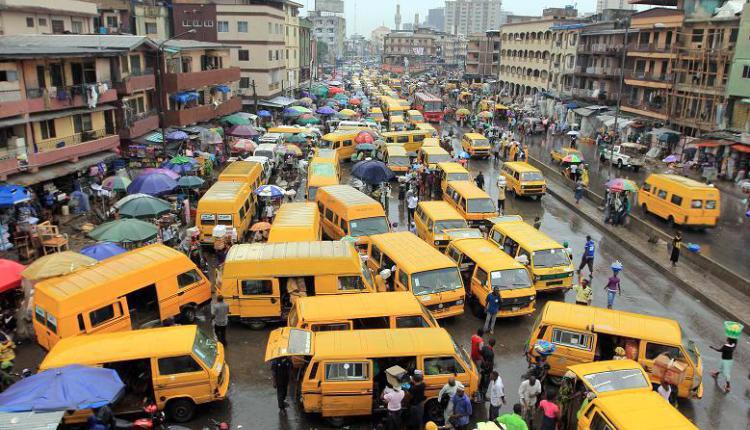

I was challenged to identify how should organizations start thinking more politically. First, there needs to be organizational changes in overall values, attitudes and behavior (Unsworth, 2009). Rather than hire political economy analysts short term for ad-hoc responses, all staff must understand local politics and be willing to engage with local structures. Since there are many barriers to organizational overhaul, this is easier said then done. Major barriers include resistance from staff to engage in new ways of thinking and pressure from donors to deliver timely solutions to complicated issues. A solution that could address these barriers would be hiring more individuals with backgrounds in political science. Hiring more local (and external) political scientists would help organizations think more politically. They could provide nuanced recommendations that economists and technical advisors may have overlooked. Regional political scientists may have a better understanding of a country’s history, interplay of formal and informal institutions and how local businesses, trade unions, and civil society engage with development (and the government). My promotion of hiring (and using) local knowledge over solely external technical expertise would potentially assist in delivering more effective and practical projects and programs.

References

Leftwich, A. (2008) ‘Developmental States, Effective States and Poverty Reduction: The Primacy of Politics,’ United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), Geneva.

Leftwich, A. (2011/12) ‘Leadership and the institutions of governance: the new frontier in the politics of development’ in Jones-Parry, R. (eds.) Commonwealth Good Governance: democracy, development and public administration. Nexus, Cambridge UK, pp. 36-39.

Unsworth, S. (2009) ‘What’s politics got to do with it? Why donors find it so hard to come to terms with politics, and why this matters.’ Journal of International Development, 21: 883-894.doi: 10.1002/jid.1625