Knowledge production is not neutral. Once we acknowledge this, it becomes easier to recognize how knowledge produces power, and how power produces knowledge. Research and policy in relation to development will continue to be static if the ‘West’ remains at the center of knowledge production.

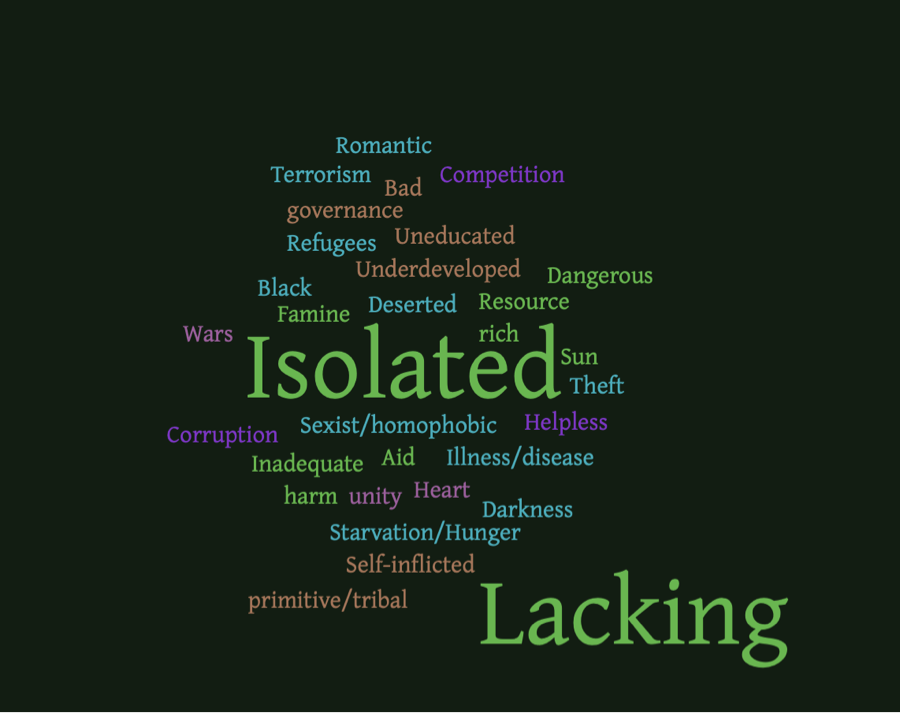

In The Invention of Africa, Mudimbe (1988) explains how Europeans have been at the center of knowledge production about Africa. Through language and art, European representations of Africans have contributed to solidifying their inferiority. This externally derived knowledge perpetuates tropes and representations of Africa:

This has led to a “number of paradigmatic oppositions: traditional versus modern, oral versus written, agrarian versus industrialized” (Mudimbe, 1998, p. 4). Consequently, ‘development’ has frequently been regarded as “transitioning from the former…to the latter” (Ibid). In turn, external and internal forces continue to critique cultural norms and attempt to remove traditional institutions to follow western development standards.

As discussed in seminar, there have been calls to decolonize the development field to break away from eurocentricity. As Mazrui (1995), I believe this requires the collapse of colonial structures, with instability being the engine (p. 32). This ‘instability’ has manifested in various forms, which have included violent and nonviolent protests advocating for increased hiring of persons of color across all disciplines in academia and the removal of colonial symbols. Today we learned about the #RhodesMustFall Movement which encompassed these specific demands to decolonize higher education.

However, simply removing a statue, increasing diversity and including colonial histories is insufficient for decolonization. While important actions, they do not go far enough. There must be greater engagement with local forms of knowledge production. For example, in many African countries knowledge has been reproduced through proverbs, song, poems, and art. Scholar Ngugi wa ‘Thiong’o has also pushed for teaching and working in non-European languages across Africa. Incorporating these local forms should assist in dismantling the inherited colonial education system (Mbembe, 1998, p. 35).

The idea of decolonizing development also forces us in the ‘West’ to question how we obtain, substantiate and measure knowledge. And what constitutes ‘Southern’ knowledge? While there is no correct answer, I think scholars who are/were primarily based in the ‘South’ present better opportunities to engage with written material that may be less influenced and perhaps more critical of Western ideologies. This is not to discredit the works of a Mazrui, Sen, or Mbembe, but an encouragement to supplement learning about the ‘South’ with the works of a Rodney, Ake, and Maathai.

References

Mazrui, A. A. (1995) “The Blood of Experience: The Failed State and Political Collapse in Africa.” World Policy Journal 12 (1), 28-34.

Mbembe, A. (2016) “Decolonizing the University: New Directions.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 15 (1), 29-45.

Mudimbe, V. Y. (1988) The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy and the Order of Knowledge. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.